The Prismatics of Silk

Abstract: Silk is so famously shimmery because of its prism-like, triangular protein structure that allows it to refract incoming light at different angles and thus to produce different colors. Yet this inherent material brilliance depends on the qualities of the silk threads and environmental conditions, like the amount and type of light that is cast upon them. I approach prismatics in this literal way, and I also expand it metaphorically to encompass the situated and contingent nature of material, bodily engagements with silks and their colors. This essay renders the prismatics of the three "mother colors" of silks that are often naturally dyed and woven in Surin, Thailand – blue from indigo, red from the lac insect, and yellow from various tree woods and leaves – to reflect upon how appreciation for and understandings of colors are inseparable from sociocultural, economic, political, and historical considerations of the colors' origins. Finally, I play with a "prismatic" structure of written fragments and flashes to capture another dimension of the idea of "prismatics."

Citation: Dalferro, Alexandra. “The Prismatics of Silk.” The Jugaad Project, 8 Dec. 2020, thejugaadproject.pub/the-prismatics-of-silk [date of access]

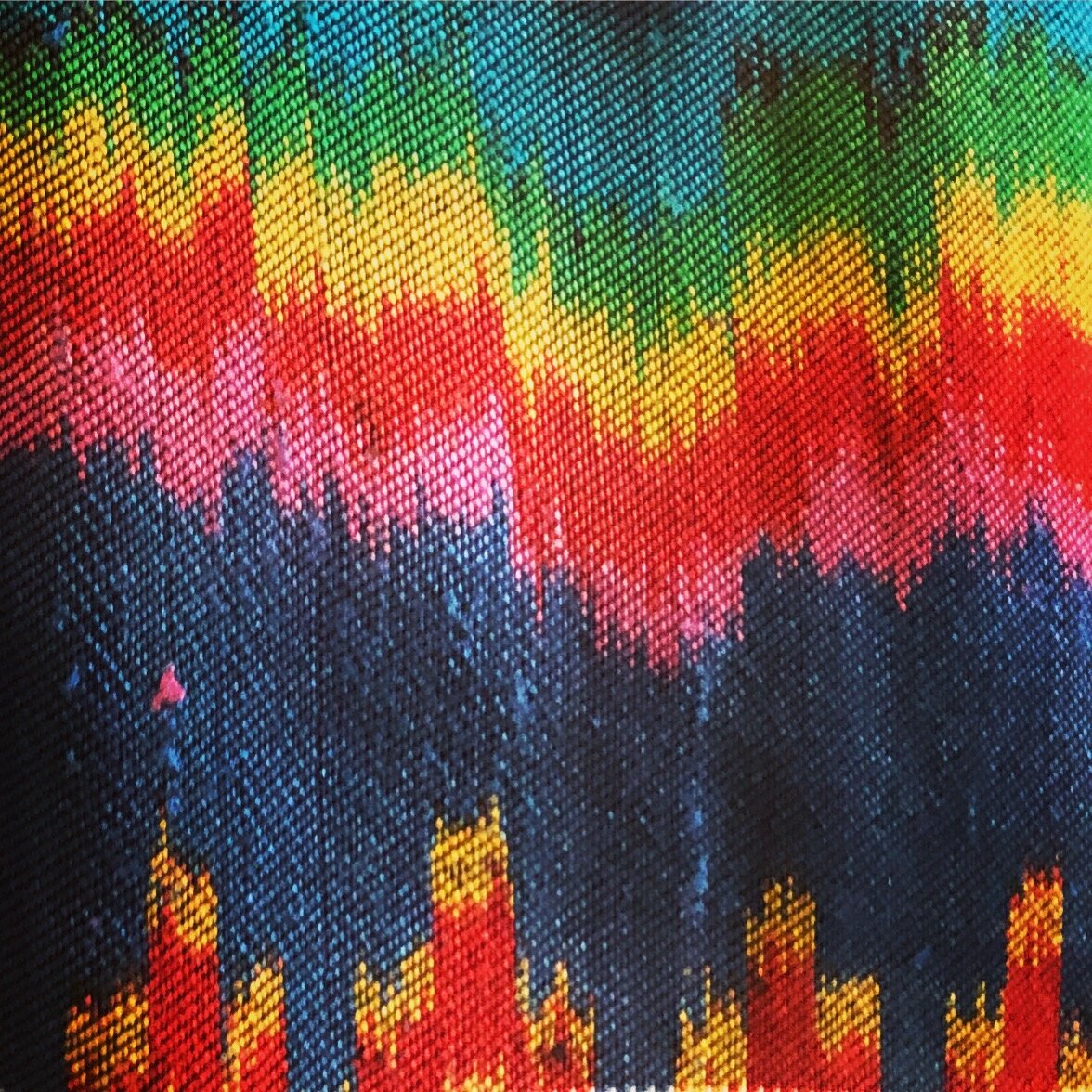

Figure 1. A piece of matmi/ikat silk woven in Surin. (Source: Author’s documentation)

Yellow, red, blue. What do they look like? Describing a color without naming other colors in the attempt is nearly impossible. Like this fragment of silk: it is buttery yellow…and scarlet red…and sapphire blue. The names themselves draw from substances and things that are so linked to the color that they ultimately stand in for it. Gold, blood, sky; lemon, cherry, cornflower; si luang dok buap (sponge gourd flower yellow, Thai: สีเหลืองดอกบวบ), si daeng met makham (tamarind seed red, Thai: สีแดงเม็ดมะขา), si nam thale (sea water blue, Thai: สีน้ำทะเล). Our own associations with and feelings about colors distill personal, cultural, political, and economic histories and positions; they emplace us as they swirl around us, hinting at lives lived otherwise, supersaturated realms of possibility like hot pink Bangkok taxis whizzing by in the night.

Sometimes, the order of colors matters, and sometimes, dizzying disorder is the point. When matmi/ikat pattern makers and silk weavers in Surin are using natural dyes, the order of the three mae si, or mother colors, makes all the difference.[1] Yellow, red, blue. Many English speakers know these colors as “primary colors,” and perhaps, as I do, they recall color wheel charts hanging on walls in elementary school classrooms, instructing pupils of wandering eyes about which colors play nice and compliment one another, which colors clash and rattle our vision, and which colors should (or should not) be mixed together to generate more colors, as though mixing orange with blue does not also produce a new color. Yellow, red, and blue combine to make green, orange, and purple, and a rainbow of hues in between.

Figure 2. Shirts for sale in Surin to commemorate the former king (yellow) and queen mother (blue). (Source: Author’s documentation)

Yellow (Monday), pink (Tuesday), green (Wednesday), orange (Thursday), blue (Friday), purple (Saturday), red (Sunday). In Thailand, the color wheel informs the wheel of time even as the wheel is flattened into a line of calendrical days that still repeat, Monday through Sunday. Each day of the seven-day week is assigned an auspicious color, a practice that comes from astrological rules that are in turn influenced by Hindu mythology. Some civil servants and workers must wear corresponding uniforms, like the docents and greeters at the Queen Sirikit Museum of Textiles (QSMT) in Bangkok, whose shimmering, Thai-national-dress-inspired, silk clothing changes color according to the day of the week. Each member of the royal family has flags and insignia with designs that are dominated by the color of their weekday of birth. A seemingly transparent formula seduces pundits and visitors; reporters love to remark that Thai people show their reverence for former King Bhumipol Adulyadej (Rama IX, r. 1946-2016) by wearing yellow on Mondays, as the king was born on a Monday in 1927.

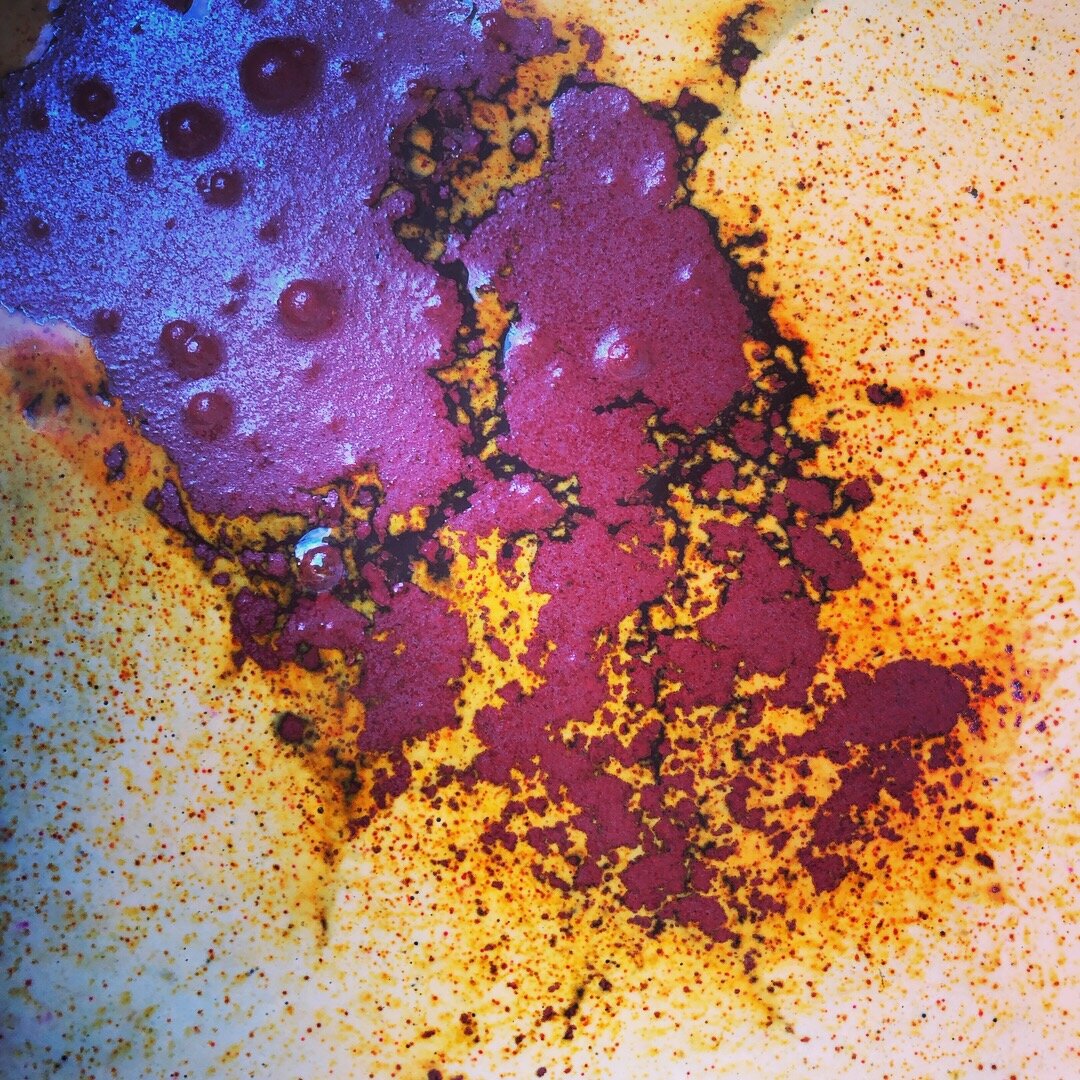

Figure 3. Matmi skeins drying. (Source: Author’s documentation)

Yellow, red, blue. The order of the colors makes all the difference, especially when patterns like hol are being knotted.

Figure 4. A Piece of hol woven in Surin. (Source: Author’s documentation)

Hol is the queen of Surin silks... the most beautiful, recognizable pattern. Now people use chemical dyes because they are easier, but I think hol is most beautiful when it is made from natural dyes. Alex, have you visited Khru (master teacher) Aromdi or Khru Gop’s workshops to see their natural dye processes? Khru Gop—his colors… I heard he mixes chemical pigments with the leaves and that’s why his colors are so bright. No one can make colors so bright with natural ingredients. He lies. And I don’t like his finished silks either. The patterns aren’t sharp.

Hol is like running water. That’s what hol means in Khmer – the same word as lai (to flow) in Thai. The stripes make the paths for the water, or something.

Figure 5. A piece of hol woven in Surin. (Source: Author’s documentation)

Hol is your favorite pattern? The colors are so dark – it’s an old people pattern. Pui remarked with disappointment. Which ones do you like? I asked. I like the patterns that only fill half of the sarong, she said. The lai prayuk (adapted patterns) in bright colors. Like lai thang duan, the pattern named after the expressway.

Hol is worn mostly by women today, Khru Gop told us as he stroked the piece of silk that he’d just spread on his table. This one is hol srei (women’s hol). The women in the audience nodded politely and admired the textile. They were members of a group of cotton weavers from Sakon Nakorn province, and they had gathered at his workshop for the weekend as part of a training to learn more about how he used natural dyes. In the old days, Surin women made silks for their families and for local rulers and they sent their silks to the courts of both kingdoms, Siam and Khmer. Some patterns could only be worn by men, like hol phroh (men’s hol). He unfurled another piece of silk with flourish and placed it beside the hol srei. I’d seen Khru Gop give this mini lecture before; he fussed with the two silks and prepared for his big reveal. The hol phroh was dyed in the same deep red as the hol srei, and from where I sat at the edge of the crowd, they blurred together, achieving too well the effect he desired. Surin women were very clever, he continued. They used to make hol phroh for the men and they wanted to wear it too, because the matmi (ikat) pattern was so beautiful and complex, but they were forbidden. So they knotted the same pattern into a matmi skein, but when they wove it, they divided it into sections that they separated with these stripes. See? That way, they could wear the hol phroh pattern, but it was hidden. The women drew closer to examine the subtle similarities that he pointed to on the cloths. Versions of this story are recited often among weavers in Surin, sometimes as they woo potential customers at the weekly Green Market and sometimes as they entertain students and researchers and anthropologists who sit with them as they tie knots into bunches of silk to make more hol.

Figure 6. Hol srei (left) and hol phroh (right) at Khru Gop’s workshop. (Source: Author’s documentation)

When a matmi pattern-maker and weaver like Mae Nid begins to tie knots on bunches of weft threads in a configuration that will become hol, she submerges her skein of silk in a yellow dye bath. The silk that is held tight by the knots she has already tied will remain white, while the non-knotted threads will be saturated with hot liquid sun. We make this liquid by boiling water and khe wood (Thai: เข, English: cockspur thorn, Science: Maclura cochinchinensis) that we buy by the kilo in Surin town. Sometimes instead of khe, Mae Nid uses the pra hot plant (Khmer-Surin: ประโฮด, Thai: มะพูด, Science: Garcinia dulcis) and the khanun tree (Thai: ขนุน, English: jackfruit, Science: Artocarpus heterophyllus).

Figure 7. The surface of a chemical yellow dye bath. (Source: Author’s documentation)

Figure 8. A natural yellow dye bath made with khe wood. (Source: Author’s documentation)

At 60 baht (~$2.00 USD) per kilo, the khe chips are much cheaper than other natural dyestuffs like khrang (red) and khram (blue/indigo) available at silk supply shops in town, and for this reason yellow is a popular color to make at the frequent natural dye trainings held in Surin and sponsored by government agencies. In the “color theory” components of these trainings, participants like Mae Nid are encouraged to design for the international market, with “international” always the slippery metonym for Western; training facilitators emphasize farang’s preference for dark colors like navy blue and black and for items of clothing with only one or two colors.[2] A facilitator once noted how these somber predilections contrast with those of Thai people, who like lots of colors and patterns that she described as si jaes – jazzy colors. Intractable Western chromophobia may be linked to longue durée associations of bright colors with primitiveness and the appearances of colonized subjects, and to fear of the full pleasure of submitting oneself to the unpredictable flows and vibrations and crashes of color “jazz.”

Figure 9. Detail of a matmi silk woven in Surin. (Source: Author’s documentation)

Over the past ten years, the demand for natural dyes has surged in Surin and in textile-producing communities across Thailand; global “go green” trends have inspired middle- and upper-class consumers to sacrifice the candy-bright hues of chemical pigments for the usually more subdued, earthy tones of natural dyes, which producers market as “organic,” “traditional,” “from nature,” and the result of “local wisdom.” These labels belie realities of supply chains, dye recipes, and village histories – dyestuffs are often gathered in unsustainable, non-regenerative ways in faraway places, mixed with chemical mordants, and boiled into vats by members of weaving groups who are dyeing with natural materials for the first time, guided by “experts” trained as scientists who work at research institutes in Bangkok and other large cities. The virtue of making and consuming “natural” colors is not diminished by these inconsistences, unless they are made too obvious, as in the case of Khru Gop, whose “natural” colors are so vivid that few think they are “real.” This accusation is both technical and ethical. Unlike some other master weavers in Surin who tend to believe that their respected position requires them to share their knowledge and thereby perpetuate these historically and culturally significant practices, Khru Gop refuses to reveal his methods to those outside of his small weaving group, and his silks are priced so high that few people in Surin can afford them. Naturally dyed silks are always more expensive than their chemical counterparts; while two meters of lower quality, simply patterned, chemically dyed silk can be purchased in Surin for around 1,000 baht or ~$30.00 USD, a high quality, two-meter piece of naturally dyed silk sells for at least 3,000 baht, or ~$100.00. A piece of Khru Gop’s silk costs about 30,000 baht, or ~$1,000.00 USD.

Figure 10. A natural dye training in Surin where dyeing with mud is being demonstrated. (Source: Author’s documentation)

Price is but one measure of silk’s value in Thailand. Woven in the region for over 1,000 years, silk textiles were traditionally key tributary gifts and offerings exchanged among kingdoms, bestowing rank and status and embodying political and social hierarchies. Today, silk has become a powerful symbol of “Thainess” and of enduring cultural heritage, and the material is closely linked to Queen Sirikit, whose efforts to safeguard the village-level production of silk and other textiles and handicrafts since the late 1960s are immortalized at the QSMT. Yellow, blue, and purple versions of hol are woven every year in Surin to commemorate the respective birthdays of the former king, queen (Friday: blue), and Princess Sirindhorn (Saturday: purple). One type of hol is even named after the princess. Hol prathep, or Angel Hol, bequeaths Sirindhorn’s nickname to Surin’s most famous pattern. A weaver from Sawai Na Haew village created a variation of the traditional hol pattern with the intent of offering the finished silk to the princess, and after she did this, the pattern was circulated and reproduced among weavers, always referred to with this name.

Figure 11. Hol Prathep. (Source: Author’s documentation)

Once at a weaving training, I sat beside an older participant and we searched the chemical dye color charts in vain for si prathep, or angel color; the auntie was looking for the perfect shade of purple to dye and weave her silk in honor of the princess. The princess is an angel and is purple, just as the former king is a god and is yellow. Though yellow must come first as the base for mixing, the ground for hol’s ruby reds, it is rarely a dominant color in the body of patterns that has been passed down over generations and is associated with Surin’s Khmer-speaking communities.

Figure 12. A rainbow array of hol-patterned silks woven by members of Mae Nid’s weaving group. (Source: Author’s documentation)

Yellow makes way for red that comes from khrang. Mae Nid removes some knots and adds some knots to her hol pattern; the additions cover up and preserve the golden yellow of the kae for now, and the places where the knots have been cut away will soon be awash in red that glimmers ripe orange from the first layer of yellow.

Figure 13. Detail of a matmi pattern in progress; yellow and red have already been dyed. (Source: Author’s documentation)

Khrang (Thai: ครั่ง, English: lac, Science: Kerria lacca) is the name of both a type of scale insect and the secretions that result when female insects bore their proboscis into the soft wood of the jamjuri tree (Thai: จามจุรี, English: rain tree, Science: Samanea saman) and suck food from it. After eating, they discharge resin that covers their bodies like scales and gradually accumulates to become their nests.

Figure 14. Khrang for sale outside of a weaving supply shop in Surin town. (Source: Author’s documentation)

The insects hide themselves and their larvae in the knobby brown homes that fuse to and camouflage into the tree branches, and among some Khmer people in Surin, liak (Khmer-Surin: เลียก, Khmer: លាក់) is still thought to be imbued with the capacity to conceal and reveal. At phithi ban mai, or new home blessing ceremonies, a piece of lac is sometimes present among the ritual offerings to prevent against loss of the home. Similarly, pieces of lac are tucked into cabinets that contain valuables, because if a thief enters the home, the powers of the lac will keep the precious belongings hidden from view. The Khmer word for khrang, liak, sounds like the English “lac” and French laque, but it also means “to hide.” The ruby red hue that characterizes Surin silk patterns like hol, amprom, lai sarong srei, and many matmi designs traditionally comes from khrang/liak dye but today is also easily achieved with chemical dyes. Lac is increasingly hard to find locally; massive jamjuri trees are cut down to make room for construction projects, or they are greedily stripped bare by khrang-seekers who do not bother to leave any branches behind so that the insects can continue to propagate.

Figure 15. Straining color from pounded khrang. (Source: Author’s documentation)

On hol silks, khrang hides yellow with ease, but sometimes colors that blend well on the wheel and on the skein clash violently in other circumstances.

Hol is what Yai (Grandmother) See and Yai Thuang and Yai Ruang wore when we flew from Buriram to Bangkok on AirAsia’s 45-minute, 6:00 am flight because the group of five grandmothers from Saen Suk, Surin, wanted to ride in an airplane for the first time. Their daughters dropped them off, one-by-one, at the village shrine at 4:00 am and told me to take care of them, and the Yais prayed at the shrine, asking the village spirits for permission to travel and protection on the journey. P’Trop, Yai Kan’s daughter, drove us all to the airport in her car. At the check-in counter I presented their national ID cards, and Yai See joined me to hand over her passport proudly. She had been to Vietnam a few years ago to sell silk, but she didn’t fly there, she traveled in a van, she noted. Yai Kan and Yai Ploy didn’t wear hol but they had selected other Surin-patterned sarongs in the same shade of red, and on the plane, we took up two rows, forming a red mass that shimmered with nervous excitement.

Figure 16. Taking off from Buriram. (Source: Author’s documentation)

In Bangkok, we stopped to rest at the apartment I had booked for the night, and the Yais chose their bedrooms and unpacked their overnight bags and switched their cotton tops for silk ones to match their sarong skirts. We radiated red from head to toe – I was hurriedly dressed by Yai Ruang in her extra set of clothes when she realized (with dismay) that I had not brought any Surin silk to wear on the trip. When navigating the narrow sidewalks as a slow column, office workers and street cleaners and fruit sellers paused to watch and to admire:

Later, when we crowded into the BTS Skytrain, bodies pressed close as the usual polite distances between surfaces and scents collapsed, a passenger saw our silks, wrinkled her nose, and glared at us. Or maybe she wrinkled her nose first, then saw our silks, and then glared. Whatever the order, Yai See and I had been watching, and Yai See’s jaw was tight as she held the woman’s gaze, refusing to make herself small in this train car not usually filled with (dark skinned, Northeastern) people like her.

Figure 17. On the Chao Phraya River Taxi. (Source: Author’s documentation)

We took the BTS to the Chao Phraya River Taxi and rode the murky waves to the Grand Palace and the Temple of the Emerald Buddha. Some of the Yais had visited recently with their families before the cremation of the former king, wearing hol dyed black per the year-long mourning period dress mandates. There are more Chinese tourists here than farang! they all marveled. We found some empty steps and sat down for a break. Yai See remembered how the crowds were not as thick when they ma pen mob (came as part of a mob). That time, they slept on mats at Sanam Luang for ten days but grew bored hanging out there for so long, so they ventured to the temple for fun. Ma pen mob??? ………

The trip was sponsored by a local politician from Saen Suk for supporters of exiled, former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra. They all took a bus together to Bangkok and wore red T-shirts with political slogans paired with their silk sarong skirts. It was before the people were killed by the army, before all the people died at Siam Square, they said. Yai See wanted to be there but refrained from identifying herself as a red shirt – a sua daeng – as such overt identifications in a country with “color-coded politics” and an authoritarian prime minister in power can be risky. Many supporters of red shirt leaders and platforms ardently hope that yellow gives way to red, or that the entrenched royalist-nationalist model supported by the yellow shirts, in which a few moral and virtuous men know best and make decisions on behalf of the populace, is replaced with full representative democracy.

Figure 18. Posing at the Grand Palace and Temple of the Emerald Buddha in Bangkok. (Source: Author’s documentation)

Hol is the fabric of choice for Yingluck Shinawatra when she visited Surin as Prime Minister in July 2012 and, wearing an expertly tailored hol jacket and hol sarong skirt, made offerings to monks who sat atop elephants amidst throngs of fans and curious locals.

Figure 19. Yingluck in Surin in 2012. (Source)

Blue, or indigo, or si khram (Thai: คราม), comes next, the final true blue dye bath that is considered by many to be the hardest to make and allows strips and spots of vegetal green and turquoise and sea water blue to emerge on hol silks when knots have been removed and khram washes over shades of yellow, or when it seeps into areas kept white and reveals the depths of its blueness. When dyers make indigo from scratch, they pick fresh plants and soak them in cool water for two or three days until tendrils of yellow-green pigment whisper into the water and rise to the surface as a mass of bubbly blue foam, like an iridescent bauble trembling on the surface.

Figure 20. An indigo vat bubbling in Surin. (Source: Author’s documentation)

Indigo vats must be liang – cared for – the word liang (Thai: เลี้ยง) connotes acts of nourishing and nurturing and is the word used for raising a child. Mae Nid is making indigo for the first time, and she calls her friend in Kalasin province for help. He tells her to imagine that the indigo is a beautiful woman who she must “sniff kiss” (hom gaem) often for best results.[3] We look at each other and roll our eyes and feed the frothy vat with nam makham (tamarind water) and nam dang (alkaline water) made from coconut husk ash that we taste beforehand, tiny drops on our tongues to make sure it is properly salty. When a pungent smell begins to arise from the mixture, we inhale deeply, sniff-kissing the air and emphasizing how good it smells (hom); according to Mae and other indigo dyers, commenting on the odor as foul or unpleasant can cause the indigo to spoil and not transfer to the silk.

Mae’s first attempt at indigo fails; the blue stays in the pot and won’t stick to the silk. The skeins are murky gray – not the right color. She will try again, she says, and then she begins to see indigo everywhere. During a ride on her motorbike we glimpse a flash of electric blue in the fields, a bird teasing us with the fleeting beauty of its blue-feathered flight. That bird is the color of khram, Mae says. That bird is the right color. Making silks that are the “right” colors preoccupies Mae Nid and other dyers and weavers in Surin, and concern over color correctness extends to other realms, too. When we walk down the dirt road that winds around the houses in Mae Nid’s small village, her neighbors call out, Look at that brown cow and that white cow walking together! Mae’s skin is deep brown and she mentions it often, especially when I am around to heighten the contrast. Her 90-year-old uncle whose eyesight is nearly gone asks Mae where I am from, and she tells him, America! then points to her young daughter and herself and flippantly adds, We are from Ethiopia! Another time when we are using mineral-rich river mud to darken the color of light pink khrang bundles of silk, Mae holds up her mud-caked arms and notices how her skin underneath is the same color. I always balk and stammer at her jokes – are they insensitive? Racist? Self-deprecating? Subversive? All of these things, or none of these things?

Figure 21. Wringing out mud from a skein of silk. (Source: Author’s documentation)

I endeavor to untangle the strands of my own discomfort, partly shaped by American histories, understandings, and present realities of racial difference and hierarchy that influence global structures of oppression and standards of beauty. Simultaneously, I encounter these dynamics as particular and distinct, a colorism that functions to rank and refract a group of people who seem to share the same racial identification but occupy a complex, discriminatory palette. Colorism works differently in different places, but a constant feature tends to be the logic of the color gradient – the lighter (whiter), the better. This visual evaluation of phenotypic qualities that supposedly correspond with inner states coalesced into a cross-cutting ideology during the period of colonization in Southeast Asia. Faced with increasing French and British acquisition of land in Indochine, Burma, and Malaya, and Western discourses of race, which threatened the legitimacy of Siam’s multi-ethnic, tributary empire and exposed the kingdom’s potential vulnerability to colonization, King Chulalongkorn initiated a territorializing project to incorporate Siam’s ethnic Others, like the Khmer people in today’s Surin, as “Thai,” situated within a bounded nation-state. Originally an ethno-linguistic label used to describe T’ai language family speakers, “Thai” has retained this meaning and gradually expanded to encompass and conflate notions of nation, nationality, race, ethnicity, and citizenship. These categories are all captured by the term chat (ชาติ). [4] Prior to and alongside this framework, people in Thailand have long associated lighter skin with beauty, wealth, and the ability to stay indoors away from the hot sun, unlike farmers who grow dark beneath its rays. Everything from economic class and social status to education level and moral character can allegedly be discerned by the color of one’s skin, and people from Thailand’s Northeastern region, where Surin is located, are regularly stigmatized for colors that they can’t control. No one wants to come to Surin because they are afraid of all the people with black skin (phio dam), one local business owner tells a group of visitors from Bangkok. The next day, Khru Aromdi, a master weaver and natural dyer from Surin, gives an indigo dye demonstration for these visitors and for members of his weaving workshop. He leaves the skein of hol-patterned silk in the vat for a long time, and someone urges him to remove it lest it turn too dark. Not yet, he says. I want it to be as beautiful and dark as the skin of Surin people.

Figure 22. An indigo vat in Surin. (Source: Author’s documentation)

Mae Nid forgoes the ever-expanding array of creams and serums that promise to whiten not only the face, arms, and legs, but also the armpits and nipples, preferring to keep her skin smooth with baby powder and never forgetting a slash of bright red lipstick before going to meetings and trainings. Whenever I catch sight of her applying her lipstick at the vanity mirror in the main room of her house, she grins and calls out, Ja tuk ja paeng pak daeng wai gon (Thai: จะถูกจะแพง ปากแดงไว้ก่อน) the canny rhyme expressing something like, Maybe I’m cheap, but my red mouth is classy. Red gives Mae a surge of confidence when darker colors threaten to take it away, but Mae’s rhyme also conveys how red lips are not necessarily universally appropriate. Despite a general acceptance of “jazzy” color combinations and designs that many farang might deem “loud” or “gaudy” – subjective and enculturated judgements with which this chromophilic author vehemently disagrees – the embrace of jaes has its limits. Light and bright mixed with dark and black and stripes and swirls are OK for articles of clothing; home and commercial interiors and exteriors; sacred shrines overflowing with offerings of marigold blossoms and glittering dancer figurines and bottles of ruby-red and emerald-green Fanta soda; heaps of sticky rice turned green and purplish-blue with pandan leaves and butterfly pea flowers; and myriad other spaces and things that cause visitors and locals alike to become delightfully intoxicated by Thailand’s kaleidoscopic colorscape. And yet the boundary is drawn at the skin, and through the ways the color of the skin colors perceptions of what people use to cover themselves. Sometimes if a Thai person of a particular complexion appears in clothing or makeup that is deemed too splendidly vivid for the time and place, they may be mocked as being so Lao – very Lao. This dismissive and disparaging ethnicized accusation asserts central Thai superiority over ethnically minoritized Thai subjects, such as the inhabitants of the Northeast region, or Isan, who may self-identify as Isan, or Lao, or Khmer, or Kui, among many other possibilities, and who may claim multiple and overlapping ethnic identifications depending on context. These forms of self-description are still usually buttressed with “Thai,” like when Mae Nid tells people she is khmer tin thai – a Khmer person on Thai land – or when she emphasizes that she is a Thai person who can speak Khmer, and Lao too. So Lao is code for darker skinned, lower class, unsophisticated countryside people whose sense of the correct times and places for jaes is underdeveloped, in contrast with unmarked proper “Thainess,” bearers of which possess light skin, perspicacious attunement to surroundings, and physical features that, according to today’s standards, exemplify white Euroamerican and East Asian characteristics that are also shaped by local aesthetic regimes. [5]

Figure 23. Hands working together to remove knots from a skein of hol. (Source: Author’s documentation)

Hol is made from yellow, red, and blue, the three mother colors, even if today, chemical shortcuts replace natural ingredients to make dyeing, selling, and wearing silk easier. In this knotted and knotty configuration, colorful excesses are respected and relied upon as they overlap and combine to form a pattern that is culturally and historically significant in Surin, especially among Khmer people, many of whom associate hol with the leaves, barks, and bugs that give it its hues, and with the ingenuity of Surin women weavers, who used these hues to mask a male pattern with green and blue lines that connect the past to the present and future. Hol’s colors might change with the royal birthday calendar or the day of the week, but Surin people know that the true color of hol, the Queen of Surin silks, is red.

Mae Nid wears hol to the temple, to local cultural festivals, to ordinations for young monks, to weddings, and to other religiously significant or special and joyous events, and her husband wears a mandarin-collared shirt made of hol when he joins her on these occasions, or attends meetings in his role of village headperson. Mae Nid’s teenage son’s friend makes thigh-high go-go boots from hol that she wears paired with a little black dress when she hosts the Miss Ladyboy Surin 2018 competition, and her son designs evening gowns made of hol for class assignments as an undergraduate in the Faculty of Textiles at his university in Surin. Mae puts on her hol sarong woven by her mother, pairs it with a lacy blouse or a pink cotton t-shirt, checks the mirror, and says to me, Mae suai yang ni la. This is my kind of beauty.

Figure 24. Wearing hol at the ordination of a young monk. (Source: Author’s documentation)

Endnotes

[1] Ikat (Thai: matmi, มัดหมี่) is a dyeing technique used to pattern textiles that employs resist dyeing, or methods that “resist” or prevent the dye from reaching the yarns prior to dyeing and weaving the fabric. In ikat/matmi, the resist is formed by binding individual yarns or bundles of yarns with tight wrappings or knots applied in the desired pattern. The technique is called ikat in English, which is an Indonesian word that means to tie or to bind; similarly, in Thai, mat (มัด) means to tie.

[2] Farang is a term used for white Westerners or Western ways of doing things.

[3] A “sniff kiss” is a way of showing affection and warmth towards close friends, relatives (especially children), and romantic partners and is permissible to do in public as a greeting. To give this kind of “kiss,” one gently presses their nose against another’s cheek and gives a short sniff. The sniffs can vary in duration and intensity depending on the emotions one wishes to convey.

[4] For historical analysis and deeper discussion of these nuances, see: Strekfuss, David. “An ‘Ethnic’ Reading of ‘Thai’ History in the Twilight of the Century-Old Official ‘Thai’ National Model.” Southeast Asia Research 20 (3), 2012, 305-327.

[5] According to Jaray Singhakowinta, assistant professor of sexuality studies at the National Institute of Development Administration (Bangkok), heroines from Thai classical literature who are considered beautiful are described as having fair complexions, as though they are painted with gold. Thus, even the shade of “white” that is considered as the ideal standard has shifted over time. More recently, due to Western and Korean influences, pinkish white is the preferred shade (Salvá 2019).

References and Further Resources

Napat Chaipraditkul. “Thailand: beauty and globalized self-identity through cosmetic therapy and skin lightening.” Ethics in Science and Environmental Politics 13, 2013, 27-37.

Salvá, Ana. “Where does the Asian Obsession with White Skin Come From?” The Diplomat, December 2, 2019. https://bit.ly/2S61OJh

Strekfuss, David. “An ‘Ethnic’ Reading of ‘Thai’ History in the Twilight of the Century-Old Official ‘Thai’ National Model.” Southeast Asia Research 20 (3), 2012, 305-327.

Thongchai Winichakul. “The Quest for ‘Siwilai’: A Geographical Discourse of Civilizational Thinking in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century Siam.” The Journal of Asian Studies 59, no. 3, 2000, 528–549.

———. “The Others Within: Travel and Ethno-Spatial Differentiation of Siamese Subjects 1885-1910.” In Turton, Andrew, ed. Civility and Savagery: Social Identity in Tai States. London: Curzon Press, 2000, 38-62.

QSMT Booklet. The Queen Sirikit Museum of Textiles, Bangkok, Thailand. 2012.

Reeder, Matthew. “The Roots of Comparative Alterity in Siam: Depicting, Describing, and Defining the Peoples of the World, 1830s–1850s.” Modern Asian Studies, 2020, 1–47.

Vail, Peter. “Thailand's Khmer as 'invisible minority': language, ethnicity and cultural politics in north-eastern Thailand.” Asian Ethnicity 8(2), 2007, 111-130.