A Drawing Out: Visibilizing the Labor of Care, Enacting Mutual Aid

Abstract

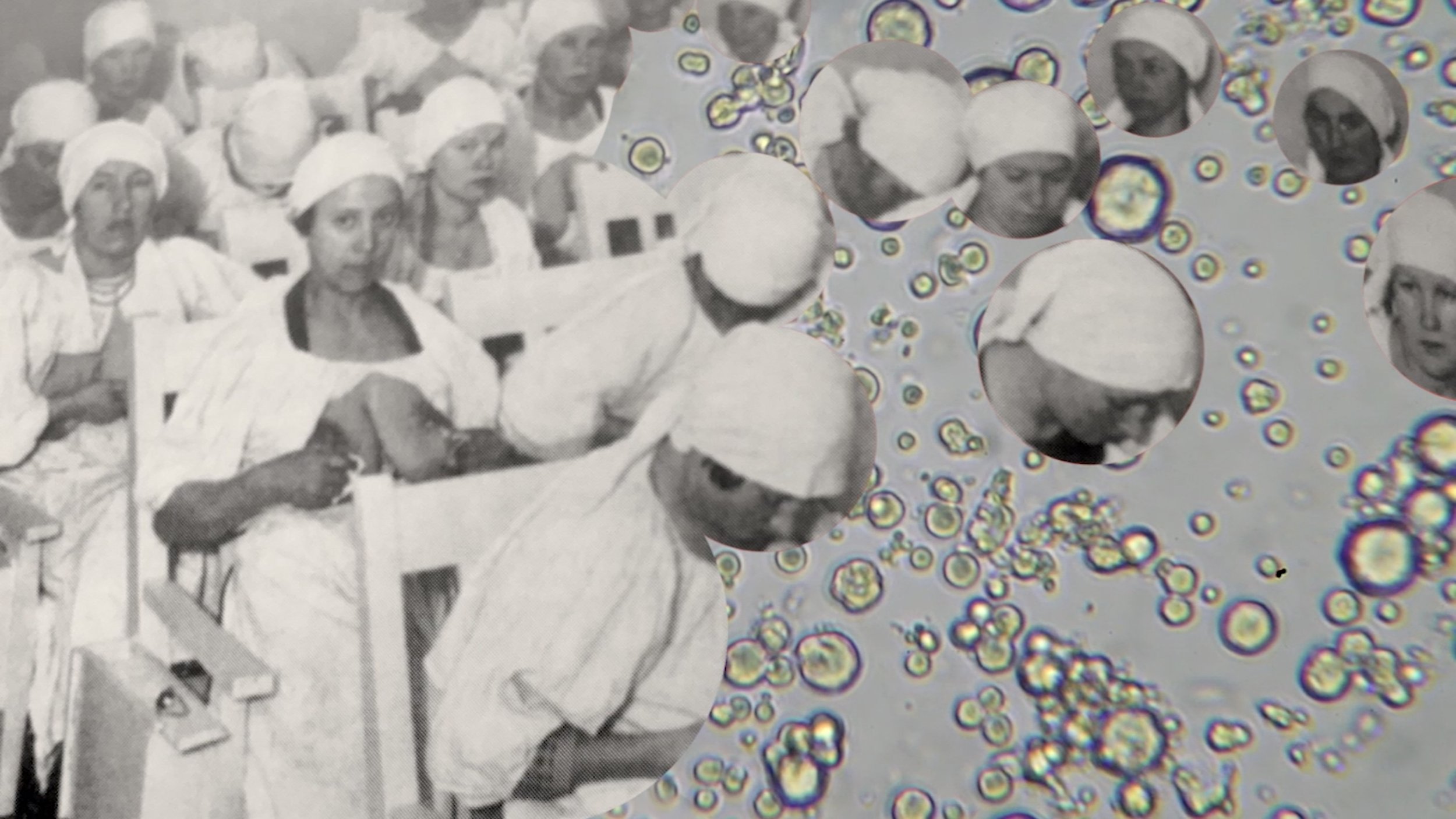

Focusing on her collaborative performance project, A Drawing Out :: Lactic Orchestration, first staged in 2018, Angela Beallor reflects upon the multiple layers of labor made visible in the inspiration for the piece: an early unattributed Soviet-era photograph depicting a group of twenty people pumping breastmilk together. This exploration develops a connection between material production and labor, represented in the photograph and enacted through performance, to contemporary mutual aid caretaking networks.

Angela Garbes, among others, has written a compelling intersectional call for valuing the essential labor of care work within the context of the current global pandemic. The term “essential labor” has become common parlance to describe labor that is often the site of caregiving without care given to the workers risking their lives during the crisis of Covid-19 (recall hospital workers dressed in garbage bags due to a lack of proper PPE). If labor is essential to the “critical infrastructure operations, " it should be valued, honored, and respected. In addition, the unpaid care work carried out in our homes, for dependent children, those living with illness, and our aged community members-- should also, as Garbes writes, be a part of this valued essential work.

This essay explores the proposals and policies for radical caretaking labor reform drafted by Soviet theorist and policymaker Aleksandra Kollontai during the Soviet 1920s. Situated between historical and political analysis, Beallor meditates on the potential of both depiction and enaction, in artistic production and collaborative performance, to help pre-figure mutual aid, collaboration, community organization, and caretaking in the current world—as we struggle to upend the current capitalist and patriarchal status quo(s).

Citation: Beallor, Angela. “A Drawing Out: Visibilizing the Labor of Care, Enacting Mutual Aid” The Jugaad Project, 19 August 2022, www.thejugaadproject.pub/drawing-out [date of access]

Angela Beallor and Elizabeth Press, Still from Cell(ular) Formation, Animation of microscopic video of breastmilk gradually revealing the Soviet photograph, 2018, part of the performance work A Drawing Out :: Lactic Orchestration.

In 2021, the stock of baby formula was dwindling, a steady decrease in supply that, by May of 2022, developed into a “full-blown national crisis.” This caretaking crisis, added atop of the crisis of the global Covid-19 pandemic, generated immense panic for those with children dependent on the formula for sustenance. Suddenly, the dietary product that families relied upon grew alarmingly scarce. A chorus of voices downplayed the dilemma on social media, advising caretakers to just breastfeed. Just breastfeed. There was a clear chasm in the understanding of how breastfeeding works, let alone the difficulties and hurdles faced by those who attempt to do so or even those who “successfully” breastfeed or chestfeed. This is shocking given that most of us have direct contact (as in we survived infancy and continued to thrive because of it) with this commonplace, life-sustaining activity.

Or is it shocking? The production of baby formula was impacted by now all-too-familiar pandemic-related supply chain woes, as well as bacterial contamination and factory closures at one of the main producers of formula, Abbott Laboratories. However, demand was also at an increased level, due to a different pandemic disruption: the diminished availability of community and familial networks vital to supporting breastfeeding caregivers had caused the rates of breastfeeding to drop significantly. Those who had recently given birth were pushed out of the hospital before their milk came in. Lactation consultants were furloughed or otherwise unavailable, having been deemed “nonessential” in the context of the pandemic. To avoid spreading infection, friends, elders, parents, and others who, in different circumstances, might stop by to assist caregivers of newborns, did not come around. The reliance on baby formula increased at this time.

The strains on these networks of sustenance reveal the uncompromisable layers of care labor— the formal and informal networks of support, paid and unpaid, familial, community, and contracted. Defined expansively: “care is at the heart of making and remaking the world”— “all the supporting activities that take place to make, remake, maintain, contain and repair the world we live in and the physical, emotional and intellectual capacities required to do so.” In the context of the Coronavirus pandemic, a renewed urgency has infused discourses of care (and carelessness). Already undervalued, this pandemic exacerbated pre-existing austerity and disinvestment into the care of children, elders, the unwell, and others requiring these kinds of inter/dependencies. The pandemic created new care dependencies of those infected with Covid-19 and/or experiencing the impacts of long Covid.

The term “essential labor” has become common pandemic parlance intended to categorize work that is indispensable to the “critical infrastructure operations” of U.S. society. Workers providing health care, working in grocery stores and meatpacking plants, cleaning, and public transport, among so many others, were suddenly invaluable, and yet continued to work often without additional compensation, while lacking basic health, safety, and protective measures. When schools, daycares, and other care centers shut down, those with waged jobs and unwaged caretaking responsibilities (children, elders, etc.) faced shrinking and difficult choices. Families were forced to choose who stayed home and who ventured to work. Laborers were forced to face the risk of infection, often risking their lives, losing their lives, and/or exposing family and community. If one was able to work from the home, the very home that one also maintained, attention was split in all directions.

What has unfolded during this pandemic has brought renewed attention to the issues caregivers and care workers face. Activist and scholar Silvia Federici has been agitating for decades about the devaluation of care-taking labor under capitalism, calling for wages for housework. These are not new ideas but rather demands that have arisen from or given rise to labor and social movements at various times in the past. During this pandemic, the lack of care shown in public policy doubled down on already vulnerable laborers. Federici notes in a recent exchange that the pandemic had revealed “the interlocking forms of vulnerability that were always present but were now affecting even the people who thought they were immune.” The impacts of this carelessness spread to those not previously impacted and the urgent discussion of these systemic problems saw a resurgence. Will it spark expansive social movement?

Perhaps this connection between the essential labor of the domestic sphere and caregiving can create new opportunities for “solidarity among caregivers, mothers, and all workers.” In the early twentieth century, Aleksandra Kollontai agitated in support of caregivers who labored both in the workplace and in the home. Kollontai was many things named and unnamed, an agitator, an orator, a writer, a Soviet policymaker, and one of the first women to serve as a state diplomat. She argued that the caregiving of motherhood (and parenting) is social and not a private matter to be left up to each individual household. Childcare is to be addressed by the greater collective of society with emphasis on the efforts to “[l]ighten the burden of motherhood for the woman worker.” Society, in her proposals, provides support to support the efforts of providing care.

While serving as the first Commissar of Social Welfare in the new Soviet society, Kollontai advocated for policies to create networks of collective creches and orphanages. Alongside women worker delegates, she called for communalization of the labor of home life. Creating canteens to relieve women of cooking duties, creches and schools to support children during work hours, collective laundries, and milk kitchens to nurse babies and provide other dietary needs for young children. Kollontai proposed a 2-ruble tax for every citizen, that would be used to fund nurseries and children’s homes as well as the support system for single mothers. Moving the tasks of the home into the public sphere to free up women from these typically “feminized” responsibilities while bringing the private and public together in the political life of Soviet Russia. Women would be freed up to participate in the envisioning and creation of the new society.

These radical visions for the domestic sphere and the work of caregiving laborers were pushed aside, however, to tend to other urgencies and visions (until wholly reversed and ended with Stalin). While creches and orphanages were constructed and expanded, these largely served those children without families. Goldman cites a critic, to sum up, the situation of the early 1920s: “‘If a mother appeals to a creche or children’s home at the present time, they tell her: ‘Your child has a mother. We only take orphans.’ They have a point: of course, we must provide for orphans first. But the mother has a point too when she thinks that deprivation, need, and birth have exhausted her, that her salary barely covers her own famished existence, and that it is impossible to work and care for a child at the same time.’”[1] Kollontai never abandoned these ideas and the debates and discussions around the collectivization of care-taking continued throughout the 1920s as is highlighted in newspapers, Komsomol (youth wing of the Communist Party) debates, studies, and cultural works from the time period.

Хочу ребëнка – I Want a Baby!

In 1926, Sergei Tret’iakov, Soviet writer and journalist associated with the Left Front of the Arts (LEF), drafted his first iteration of the play Хочу ребëнка (I Want a Baby!). This play was never realized during the lives of the writer nor the intended director, Vsevolod Meyerhold[2] but Tret’iakov places the communal nursery as a childrearing option at the center of the play’s plot. In an interview in 1927, Tret’iakov specifically stated that he wanted the play to bring “the measures of the Soviet government aimed at protecting motherhood and infancy . . . into the consciousness of women and mothers.”[3] The play centers upon a cultural worker who is communally laboring with others to establish a collective nursery.

My artistic practice engages socio-political questions at the intersection of private and public experience. In recent collaborations, I have explored themes related to caregiving, reproduction, and socio-political movement. When my partner and I decided to go through the process of having a child utilizing assisted reproductive technology (ART), I turned my artistic practice toward questions of labor and (queer) reproduction. Already immersed in studying Soviet history, I found Sergei Tret’iakov’s 1926 theatrical script and knew it would be rich material to work with alongside the ART process. My work with the script became a speculative, queer, feminist multimedia performance adaptation entitled MG (aka I Want a Baby!, Reimagined), staged in 2019.

In the play, Milda Grignau is a cultural worker dedicated to building a collective nursery who decides that she would like to birth the “perfect” proletarian without a participating father or romantic partner. Conception guided by a eugenic[4] lens is attained with the help of construction worker Yakov (who is selected by Milda), just before the play’s plot skips ahead to a future “Healthy Baby Contest” (where her child wins in a three-way tie) with no attention to Milda’s experience of gestation. Situated in the middle of Tret’iakov’s play, I Want a Baby!, is the pregnant and yet absent center of Milda’s pregnancy.

Milda’s dialogue, clearly inflected by the social discussions of gender and labor in the early Soviet experiment and policy changes instituted and/or attempted by Aleksandra Kollontai and others, explains that once she has a child, it will be breastfed by her and then sent off to the children's home. Kollontai predicted that parents would be able to take advantage of the societal support of the crèche or nursery, kindergarten, children’s homes, and schools, but still maintain “emotional bonds with their offspring.” Whenever a mother wanted to see her child, ‘She only has to say the word.’” Maternity maintained a significant role for citizens like Milda, capable of giving birth, of contributing new citizens to the new society. The capable body “was perceived as a dual-purpose machine, not just for hygienic maternity but also for paid labor within the economy,” and as such society was responsible to provide support for both tasks. Domestic laborers were to be assisted in order to engage more fully in the tasks of creating the new Soviet society.

Wholly unrepresented in the play’s script is the actual bodily experience, the labor that this process entails, the work of “birthing the new society.” Even though explicit connections are made between industrial production and human reproduction within the dialogue of the script, Tret’iakov undermines (and belittles) Milda’s labor through this void. This lack of representation is not unique to Tret’iakov’s work. The play celebrates the children borne of Milda’s labors and yet like many works

[t]he pain and discomfort of pregnancy is conveniently glossed over in NEP-era celebrations of the child, gesturing toward a future where women could be emancipated from biological compulsion, where gender as such would cease to exist. Pregnancy is depicted as something more cerebral than corporeal: It occupies the mind rather than the womb, functioning as a kind of transcendent connection to the future, detached from the messy corporeality of the present.

The play is humorous, particularly in its distance from the contemporary moment. Milda takes the unrealized visions of socialized childcare to an extreme. In Milda’s dream, the utopian vision of the collective nursery, the Palace for Children, is realized: “The days of primus stoves and poky little rooms will be long gone. Unemployment will be eradicated. The concept of the housewife will be outmoded. People won’t be on edge all the time. There’ll be a nursery. Not just a little one, though – a properly appointed one for the whole block. Sister, we will both take our little ones there. And we will be friends.”

Humorous, yes. Can it help us to consider how things could be different? Tret’iakov hoped for this. In his dramaturgical vision, he sought to present an “exhibition of standards” or, as Devin Fore writes, a “showcase of collectivity.” Tret’iakov writes, “[Sergei] Eisenstein and I were thinking about a play that would be “an exhibition of a standard person, placed in difficult conditions of action.”[5] Milda is a familiar subject placed in a difficult position. The audience was to take in the play and then leave the theatre and consider these questions as they relate to their everyday lives and the life of Soviet society.

What it takes to carry out this vital, ubiquitous labor that sustains the interdependencies of our families and communities (both chosen and blood) is overlooked and/or belittled. How to visibilize[6] this domestic labor for an audience to consider? How to agitate for care work that is honored and supported? These questions emerge in the embedded performance work A Drawing Out :: Lactic Orchestration.

Collective Lactation/Collaborative Performance in A Drawing Out :: Lactic Orchestration

My partner and I were committed to feeding our child a diet predominately of breastmilk for at least the first year. When at seven months, my child was diagnosed with “failure to thrive,” we followed many paths to many resources to try to fully resuscitate my breastmilk supply. At the same time, we did not want S. to be without enough nourishment. We reached out to our midwives who delivered breastmilk to us from another lactating caregiver in their network. We quickly looped into informal donor breastmilk networks. While our supply was low, other caregivers were producing enough breastmilk and had milk to offer from their freezer reserves.

For over five months, we traveled all around Upstate NY and sometimes as far south as Brooklyn, meeting donors in parking lots and parks, and picking up donated frozen breastmilk. While sometimes the milk originated from friends in our community, we mainly connected with donors via Facebook groups like Eats on Feets and Human Milk 4 Human Babies. Sometimes we drafted posts describing our situation and our request for milk donations. At other times, we replied to posts noting “milk2share,” following up with questions about drinking or drug use, medications taken, and diet. All milk exchanged in these communities is never for financial gain— the buying and selling of breastmilk are prohibited. While we were nervous about the exchange of bodily fluids without some sort of screening infrastructure like a milk bank, in the end, our trust was buoyed by the donor’s willingness to freely share milk that they also fed to their children.

Karleen Gribble describes such peer-to-peer milk exchange as “a type of cooperative mothering . . . a social system wherein women assist in the care of offspring who are not their own.” The exchange of breastmilk is, as Gribble writes, a “personal, even intimate, act,” but one that takes place in an informal network of community mutual aid. Those who pump breastmilk for their own children may produce more than they can possibly use. To keep up their supply, they must continue to pump. As an act of voluntary generosity and community care, these caregivers extend the reach of their labor, passing along their surplus to feed the children of others. What might happen if this type of “cooperative mothering” was formalized into voluntary mutual aid cooperative networks?

A Drawing Out :: Lactic Orchestration was first conceived as an intervention, a visibilization of caretaking labor, as an element within MG (aka I Want a Baby! Reimagined). This performance work, first created in 2018, became an independent piece, and documents of the performance (sound, image) are woven into the larger performance. It was inspired by a photograph of collective breastmilk pumping, found in Fannina W. Halle’s 1932 book Die Frau in Sowjetrußland (published in English translation as Woman in Soviet Russia in 1934).[7]

“In the Mothers’ Milk Center,” reprinted in Dr. Fannina Halle’s Die Frau in Sowjetrußland (Woman in Soviet Russia). Captioned in Der Staat ohne Arbeitslose (1931) as “At the collecting station for mothers’ milk” and continues with the captioned series “such stations have been organized in all industrial centers, in the village, in the newly-built towns, in the old industrial centers . . . everywhere, the State, the Commune, the Factory, looks after the children of the working masses.”

Angela Beallor with Michelle Temple, A Drawing Out :: Lactic Orchestration, Troy, NY 2018. Performed by Victoria Kereszi, Heather Marsh, and Chanda Lindsey. Photo by Elizabeth Press (EP).

Three performers enter the stage area, unzip their coveralls, and raise two flanges, one to each breast. The mechanical breast pumps have been custom outfitted (by collaborator Michelle Temple) with MEMS microphones, a microfabrication technology (think cellphone mics) that allow for the amplification of the sounds of the milk being extracted from the nipple as it flows from the breast through a valve into a receiving container. An animation of microscopic breastmilk imagery, collaboratively created with my partner Elizabeth Press (EP), gradually reveals the Soviet-era photograph.

Once the performers are ready, a pre-recorded single breath rising and falling begins to swell and take center stage, which cues the performers to begin to take a moment for themselves before they begin their labor. Although most performers utilize similar brand names of pumps, as each pumper performs, a unique sound signature is revealed by the sensitivity of the miniature microphone, revealing an audible distinction that is the result of many variables: stages of lactation, nipple size, breast shape, etc. Once each pumper/performer has been centered and heard, the volume of each individual channel begins to rise, leading to a rhythmic crescendo of the entire ensemble. The soundscape softens and gradually fades out to the unamplified sounds of the pumpers capping collection bottles, untethering themselves from their pumps, and taking the milk to their children off-stage. The pumping performance has a duration of 15-20 minutes, the same as the typical pumping session.

A Drawing Out :: Lactic Orchestration (documentation video). Angela Beallor and Michelle Temple with performers Vicki Kereszi, Chanda Lindsay, & Heather Marsh. Video projection by Angela Beallor and Elizabeth Press (EP). Live performance featuring six stereo pairs of amplified breast pumps, one contact mic, one amplified phantom pump, audio track, live mixing, and digital projection.

Just to be clear: This performance represents one cycle in a daily routine. Outside of the moments when the baby is fed directly, caregivers who are pumping must find a solitary space every 2-3 hours to carry out this activity. The breasts will become engorged, the milk supply will be disrupted if one is unable to complete this regular task. For many who are also laboring out in the world, this may be difficult. There may not be protections (despite being required by certain laws) to allow for the breaks necessary for this other type of labor. There may be harassment and intimidation. There may not be sanitary, private spaces to retreat to pump.

Negotiating breastmilk pumping while at work often exposes a worker’s private life to employers, and often at the same time an employer's discomfort, shame, lack of empathy, or worse. Pumps, designed to aid in this mundane act of sustaining life, are often advertised as “unobtrusive” and “discreet.” My child was two months old when I was invited to install a site-specific installation at the Museum of Modern Art in Cleveland, OH. Upon arrival, the curator pulled me aside and whispered to me that they “had a room for me”— an electrical closet fitted with a couple of chairs—that I could use for pumping. The discomfort was palpable, the space, though bare bones, was appreciated.

This is precisely why I was drawn to amplify the sound of pumping, to challenge the emphasis on secrecy and discretion, and to bring it out into the public sphere, as a form of performance. The repetitious rhythm shapes the pumping experience, and I wanted an audience to be wrapped in that soundscape. The performance is a way to re-invigorate the everyday in a public representation, laying the groundwork for a broadly defined labor “solidarity that can be grasped with the senses.” The pumpers visibilize this labor and demystify the process for those unfamiliar, while experimenting with collectivizing space, creating bonds and connections, while pulling their shared work from isolation.

I realized, in a much deeper way than ever before that caretaking, unlike the afterthought that it can so often be in artistic and academic life, was by necessity a central force in this artistic process. The project A Drawing Out :: Lactic Orchestration was entirely created by breastfeeding people and/or parents or those gestating life. Every step of this work had to be slowly taken in relation to the time and labor needs of caretaking. We could only rehearse in small spurts of time. Additional caretakers were present to take care of the babies and toddlers of the performing collective. Snacks and water were plentiful. Lots of breaks and lots of patience for changes of plans due to small and large urgencies. Lots of flexibility.

In March of 2020, The New Yorker published an article on a pandemic tendency toward “self-organized voluntarism” otherwise known as mutual aid. Many found themselves touched by catastrophe and need or exposed to the urgent needs of others in a new way. In the occurrence of the unexpected, those who had already been a part of mutual aid networks, solidarity work, or activism in the past, quickly sprang into action. Others found ways to plug in and assist or access assistance— “Radicalizing moments accumulate; organizing and activism beget more organizing and activism.”

These networks of mutual aid are nothing new and crop up in places where disinvestment rules, where a lack of monetary resources is met with mutual exchanges of time, energy, support, community, and commitment. It is a way to support each other in moments of need and in terms of socio-political movements, can create counter-power and community confidence that we can show up for each other. Mutual aid alone is not going to shift public policy or radically challenge the status quo but it can serve as a space to experiment with potential futures, “to create and sustain within the live practice of the movement, relationships and political forms that ‘prefigured’ and embodied the desired society.”

My collaborative work, rooted in the early Soviet experiment is out of an interest in moments of intense envisioning of different futures. Hidden within these earlier utopian ideas, we may find other (un/intentional) radical propositions that, in our return to this history, can spark new future trajectories. A Drawing Out :: Lactic Orchestration visibilizes care labor and honors the work of those in the informal network of breastmilk distribution, but it also built a short-lived, temporary community of caregivers who found support in the context of performance. Care was the ethic guiding the work. The work created a space of support, exchange, camaraderie, and solidarity. A space “[t]o protect each other, to enact and practice community. A radical kinship, an interdependent sociality, a politics of care.” Building collective experiments and experiences that can build into social movements and systemic change.

Endnotes

[1] I. Stepanov, “Problemy Pola,” in E. Iaroslavskii, ed., Voprosy zhizni I bor’by. Shornik (Moscow: Leningrad, 1924), 207. Cited in Goldman, 76.

[2] The play was censored by Glavrepertkom in 1927, approved for production, as a discussion play, to be directed by Vsevolod Meyerhold, and yet was delayed indefinitely as the creative authors awaited the construction of Meyerhold’s new theatre. It never saw the stage during Tret’iakov’s and Meyerhold’s lives and the original script was only recovered in Russia by his surviving wife, Olga Viktorovna Tretyakova-Gomolitskaya, in 1956. Glavnyi repertuarnyi komitet, initially created within the Commissariat of Education, the Chief Committee for the Control of Repertoire, a body of the Party for determining what works were acceptable for theatrical production. Anna Tamarchenko, “Theatre censorship,” Index on Censorship 9:4 (1980), 23. Tret’iakov was arrested and killed in 1937 and his books, papers, and works were scattered. According to his stepdaughter, his surviving works were held in the library’s special custody until 1956. He was not rehabilitated until the 1960s. Tatiana S. Gomolitskaya-Tretyakova, “O Moyem Ottse” [About My Father], in Strana-Perekrestok: Dokumentalʹnaia Proza, Sergei Tret’iakov (Moscow: Sovetskiĭ pisatelʹ, 1991), 554-563.

[3] Alexander Fevral’skii, Slyshish Moskva?!, 198. Quoted from: М. Б-де, Хочу Ребенка. К постановке в Театре имени Мейерхольда. (Беседа с автором пьесы С. М. Третьяковым).-- "Программы гос. академических театров" М., 1927, № 4, стр. 12.

[4] “Eugenics always had an evaluative logic at its core. Some human life was of more value—to the state, the nation, the race, future generations—than other human life, and thus its advocates sought to implement these practices differentially.” Alison Bashford and Philippa Levine, eds., The Oxford Handbook of The History of Eugenics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 28.

[5] Sergei Tret’iakov, “Dramaturgischeskiye zametki [Dramaturgical Notes, 1927],” in Slyshish’ Moskva. Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1966.

[6] I use visibilize as opposed to represent. This is an attempt to create space from the neoliberal tendencies in representation to individualize experiences as well as means to address them. I am interested in visibilizing what is clearly there to consider connections to broader political dialogues and collective action. The solitary action of one person, representing themselves, by posting an empowering breastmilk pumping image on social media vs. attempting to connect to the broader networks of labor, address systems of power, and collectively challenge, disrupt, or change them.

[7] The reproduction in Halle’s book is an uncredited photograph of a photograph and was likely found in the 1931 book Der Staat ohne Arbeitslose: drei Jahre “Fünfjahresplan” (The State Without Unemployment: Three years of the Five-Year Plan), Ernst Glaeser and Franz Carl Weiskopf, a collection of photographs curated from the illustrated magazine Ogoniok (Moscow) and Unionbild (Berlin). Captions in both books do not provide a thorough description of the image: who took it, where it was taken, who is depicted in the photograph, etc. Glaeser/Weiskopf’s book does provide a series of photographs and leads the viewer to surmise that this milk is then combined to feed children in a nursery, creche, or children’s home. For more on the work of Weiskopf and this book see Matthias Müller, “Rifts in Space-Time: Franz Carl Weiskopf in the Soviet Union,” German Studies Review, Volume 42, Number 2, May 2019, pp. 319-338.